The Draw Boy

“There ought to be some mechanical way of doing this job, something on the principle of the Jacquard loom, whereby holes in a card regulate the pattern to be woven.” — Dr. John Shaw Billings [1]

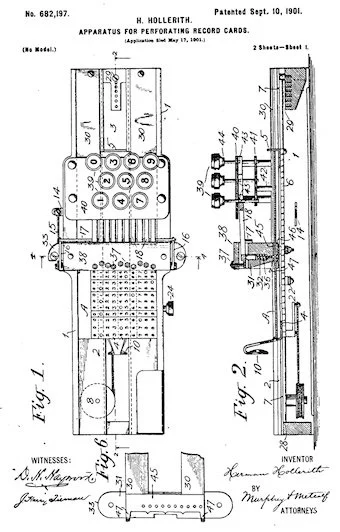

The Jacquard loom, invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in the early nineteenth century, was one of the first machines to be controlled by something resembling a stored program, namely a sequence of punched cards [2]. It wasn't a computer in the modern sense, but it demonstrated that a machine could perform complex work by following an external set of instructions, an idea that would echo through the history of computing. Jacquard's punch-card mechanism influenced Charles Babbage, who proposed using cards to control his Analytical Engine [3]. Later, Herman Hollerith used punched cards to encode census data for tabulating machines, technology that eventually fed into IBM and twentieth-century information processing [4].

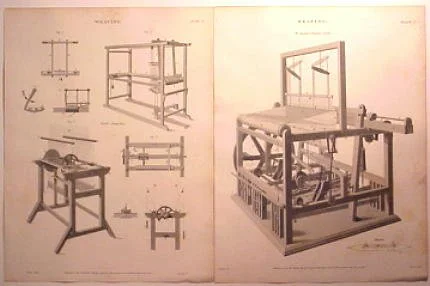

Jacquard's invention was driven by a problem: weaving elaborate patterns in silk was slow, expensive, and difficult to scale. Simple repeating designs, such as stripes, checks, and other geometric regularities, had proven amenable to mechanical improvements, a trend that would continue well after Jacquard’s invention such as The Dobby Loom from the 1840s [5]. But figurative or non-linear patterns, the kind that signaled luxury and status, such as floral brocades, remained dependent on highly skilled labor.

Before Jacquard, producing complex woven designs required a drawloom. These were large looms operated by two people: the weaver, and an assistant often called a drawboy. The weaver controlled the shuttle and the rhythm of the loom. The drawboy's job was to lift selected warp threads, sometimes in large groups, at exactly the right moment so the weft thread could pass through and lock in the pattern [6]. This was slow work with daily progress measured in inches rather than feet and yards. It was also physically punishing on the draw boy. Drawloom assistants were often young and small because the job required agility in a cramped space above the loom, where bundles of warp threads had to be lifted repeatedly for hours. The labor was highly specialized, and in the wrong hands it could ruin expensive material.

Jacquard had worked in the silk trade and was familiar with this system. Whether or not he actually served as a drawboy as has been claimed isn't clear—he was born into the Lyon silk trade, and his father was a master weaver, but it isn't definitive that he worked as a draw boy. But it’s clear he understood firsthand the constraints of pattern weaving being the physical coordination between the weaver and the draw boy, and the latter’s punishing physical work.

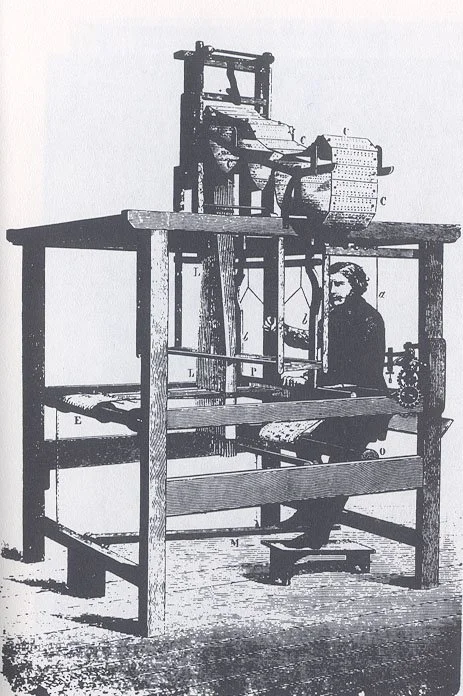

His breakthrough was to replace the draw boy with a mechanism. In 1801, Jacquard exhibited an early version of his loom at an industrial exhibition in Paris, where it attracted attention. The invention was considered impressive enough that it led to further scrutiny and development. In 1803, Jacquard was summoned to Paris for evaluation and refinement. By 1805, the French state backed the invention declaring it public property, and Jacquard received government support in the form of a pension and royalty-style payments tied to adoption. By 1812 there were 11,000 Jacquard looms in use in France.

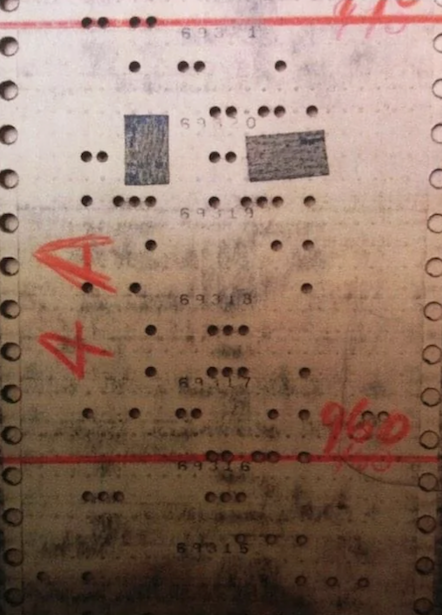

The loom itself used a set of hooks connected to harness cords, each harness controlling specific warp threads. A punched card would be pressed against a row of needles. Where the card had a hole, the needle could pass through. Where the card had no hole, the needle was blocked. This determined which hooks were engaged and lifted on that cycle of the loom [7]. In that sense, the card didn't contain the pattern as an image, it contained the instructions for a single row of weaving. One card corresponded to one 'step'. A chain of cards corresponded to a complete design.

A Jacquard pattern could thus be 'programmed' by creating a set of cards with holes punched in specific positions. Once you had that card chain, you could reproduce it, share it, or run it on multiple looms. The design became portable and scalable. It was software, of a sort, in a primitive physical form with the loom acting as a runtime. The skill and physical effort of the drawboy moved into the abstraction of the punch-card. This had two notable consequences. First, it dramatically increased productivity. A single weaver could now produce complex patterns with far less assistance, and the loom could reproduce intricate designs reliably and at scale. Patterned cloth that once required elite labor and time could now be manufactured more efficiently. Second, it introduced an information concept that would become central to computing: a machine could be controlled by a sequence of discrete symbolic instructions.

The Jacquard system is often described as 'binary'. Now, that's not wrong in a loose sense. Each possible position on the card is either punched or unpunched. There's a hole that allows the needle to pass through or no hole that blocks it [8]. It's not a computer in a formal sense, but it is a demonstration of a fundamental idea in computing: a complex output can be produced by a sequence of simple yes/no decisions. That punched-card approach survived for an astonishingly long time, well over 150 years. Variations of card-driven control appeared throughout industrial machinery, and punched cards remained a data medium in business computing well into the twentieth century, not completely phased out until the 1970s.

Jacquard's loom itself did not remain completely unchanged, but the essential architecture of hooks, harness cords, and punched-card control, proved durable. Later improvements added speed, reliability, and power. Steam power and later electric motors removed the need for human muscle entirely. Looms became faster and more automated, and industrial weaving evolved into a specialised branch of engineering [9].

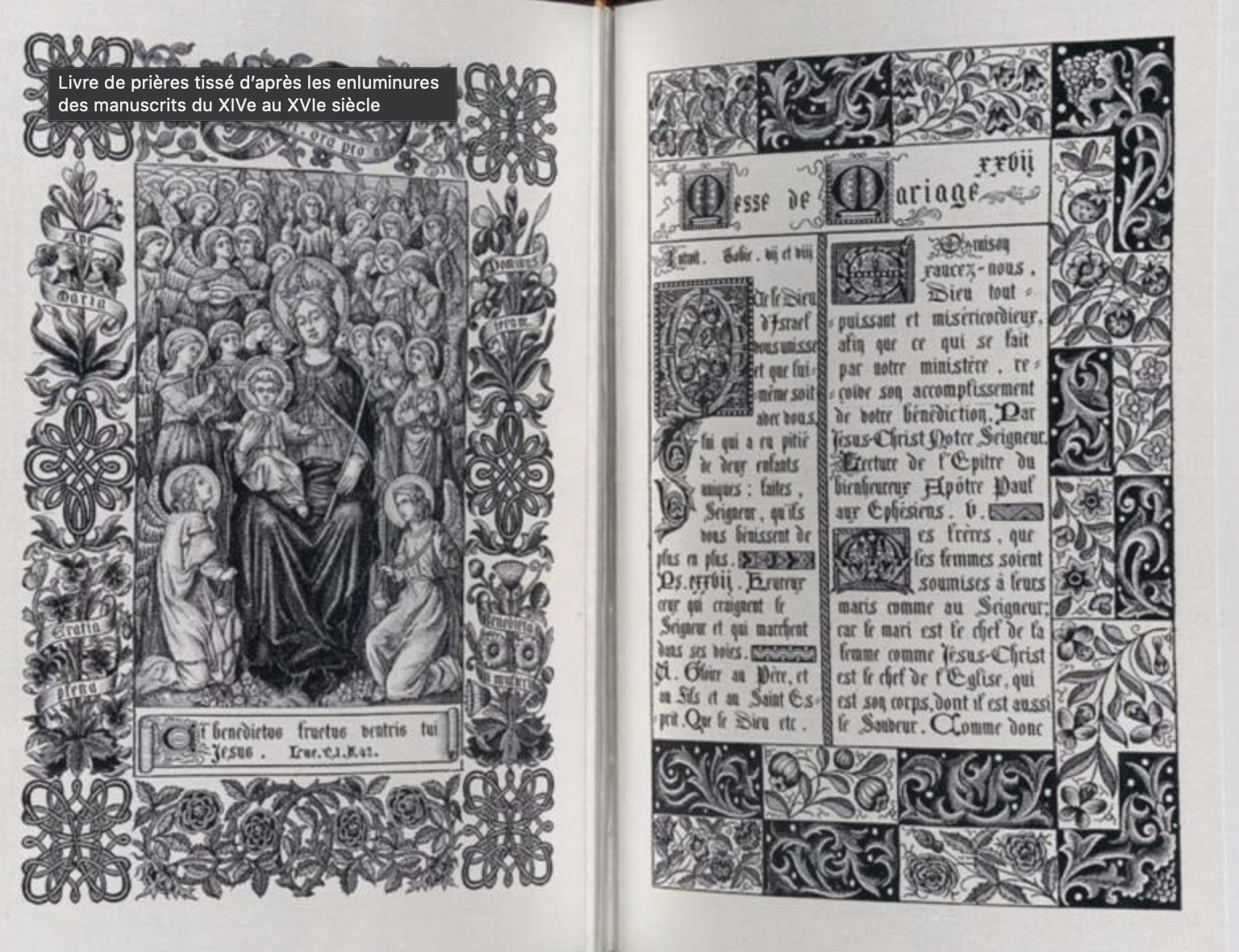

The next leaps in weaving was not merely better programming but entirely new mechanical approaches. Shuttleless looms—rapier looms, projectile looms, and air-jet looms—dramatically increased weaving speed by replacing the old back-and-forth shuttle mechanism. It wasn’t just volume and scale. The looms by the end of the 18th century could produce weaves of incredible detail, matching and arguably surpassing anything a master weaver could. A prayer book, woven in silk, called the Livre de Prières. Tissé d'après les enluminures des manuscrits du XIVe au XVIe siècle is a remarkable example. Its 58 pages are woven silk, made with a Jacquard machine using black and gray thread, at 160 threads per cm. The pages have elaborate borders with text and pictures of saints. It’s estimated up to 500,000 punchcards were used to encode the pages [10].

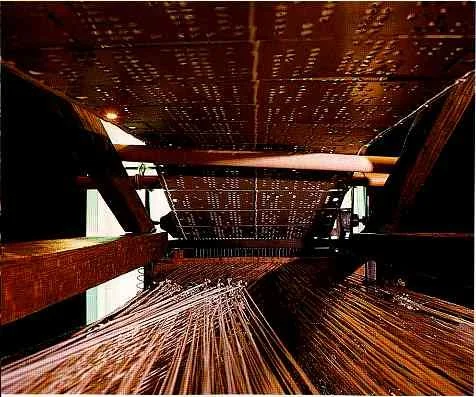

Eventually the cards themselves began to disappear. Instead of encoding a pattern physically by punching holes, the pattern could be stored digitally and fed into a loom electronically. Modern Jacquard looms are computer-controlled and can operate with thousands of independently controlled hooks, producing designs of extraordinary complexity at industrial speed [11]. Today, modern looms can insert weft threads hundreds or even thousands of times per minute, producing vast quantities of fabric with minimal human intervention. But at heart, the archetype remains: row by row, instruction by instruction, the machine being instructed which warp threads rise and which remain down.

Jacquard’s invention reorganized labor. If you no longer needed a drawboy to lift threads and were no longer gated to inches per day, you still needed someone to create the pattern instructions. The pattern itself became separable from the act of weaving resulting in new kinds of jobs and separation of labour. This gave rise to a new kind of specialist: the designer and pattern-maker, whose work in the form of pattern books could be translated into a card chain and reproduced at scale. As patterned cloth became cheaper and more widely available, demand expanded. More people could afford decorative textiles; at the same time ability to produce outstripped basic demand. And as the Industrial Revolution repeatedly demonstrated when you can manufacture large volumes, you need reasons for people to buy them. It's difficult for example to imagine modern fashion without this underpinning. Styles began to change faster. Designs cycled. Novelty became a market force, for example in the form of seasonal changes.

And what of the drawboys whose back breaking labour Jacquard's invention helped eliminate?

The Jacquard loom was not universally welcomed. To the workers whose livelihoods depended on the old system of child labour, the loom was considered a threat. In Lyon, silk workers generally resisted its adoption, and early Jacquard mechanisms were attacked and smashed and rioted against. Jacquard himself was threatened. The status of Jacquard in Lyon erected in 1840 was placed on the site where one of his loom was destroyed. The drawboy as a job vanished, and master weavers shrank drastically as value moved into automation and pattern design.

Notes

This was first written in 2006. Dusted off twenty years later as an allegory in the age of AI and also to correct some facts.

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, History: Dr. John Shaw Billings and Hollerith's Tabulating Machine.

[2] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Jacquard loom / Jacquard mechanism. Wikipedia, Jacquard Machine

[3] UK Science Museum, Charles Babbage and the Analytical Engine

[4] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Herman Hollerith. Wikipedia, Herman Hollerith

[5] Dobby is a regional contraction of Draw Boy but also a word used to describe someone small and useful in English folklore. The Dobby Border used in towels was created using a specialized Dobby loom as it allows small fixed patterns to be created. Wikipedia, Dobby Loom

[6] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Drawloom. Wikipedia, Drawloom

[7] Manchester Science and Industry Museum, Jacquard loom and punched cards

[8] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Punched card . Wikipedia, Punched card

[9] Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), Jacquard weaving and history

[10] Boston MFA, Livre de prières tissé d’après les enluminures des manuscrits du XIVe au XVIe siècle

[11] Smithsonian Museum of American History, Jacquard-related textile technology collections